Where

does money come from? How is its quantity increased or decreased? The

answer to these questions suggests that money has an almost magical

quality: money is created by banks when they issue loans. In effect, money is created by the stroke of a pen or the click of a computer key.

We will

begin by examining the operation of banks and the banking system. We

will find that, like money itself, the nature of banking is experiencing

rapid change.

Banks and Other Financial Intermediaries

An institution that amasses funds from one group and makes them available to another is called a

financial intermediary.

A pension fund is an example of a financial intermediary. Workers and

firms place earnings in the fund for their retirement; the fund earns

income by lending money to firms or by purchasing their stock. The fund

thus makes retirement saving available for other spending. Insurance

companies are also financial intermediaries, because they lend some of

the premiums paid by their customers to firms for investment. Mutual

funds make money available to firms and other institutions by purchasing

their initial offerings of stocks or bonds.

Banks

play a particularly important role as financial intermediaries. Banks

accept depositors’ money and lend it to borrowers. With the interest

they earn on their loans, banks are able to pay interest to their

depositors, cover their own operating costs, and earn a profit, all the

while maintaining the ability of the original depositors to spend the

funds when they desire to do so. One key characteristic of banks is that

they offer their customers the opportunity to open checking accounts,

thus creating checkable deposits. These functions define a

bank, which is a financial intermediary that accepts deposits, makes loans, and offers checking accounts.

Over

time, some nonbank financial intermediaries have become more and more

like banks. For example, brokerage firms usually offer customers

interest-earning accounts and make loans. They now allow their customers

to write checks on their accounts.

The

fact that banks account for a declining share of U.S. financial assets

alarms some observers. We will see that banks are more tightly regulated

than are other financial institutions; one reason for that regulation

is to maintain control over the money supply. Other financial

intermediaries do not face the same regulatory restrictions as banks.

Indeed, their relative freedom from regulation is one reason they have

grown so rapidly. As other financial intermediaries become more

important, central authorities begin to lose control over the money

supply.

The

declining share of financial assets controlled by “banks” began to

change in 2008. Many of the nation’s largest investment banks—financial

institutions that provided services to firms but were not regulated as

commercial banks—began having serious financial difficulties as a result

of their investments tied to home mortgage loans. As home prices in the

United States began falling, many of those mortgage loans went into

default. Investment banks that had made substantial purchases of

securities whose value was ultimately based on those mortgage loans

themselves began failing. Bear Stearns, one of the largest investment

banks in the United States, required federal funds to remain solvent.

Another large investment bank, Lehman Brothers, failed. In an effort to

avoid a similar fate, several other investment banks applied for status

as ordinary commercial banks subject to the stringent regulation those

institutions face. One result of the terrible financial crisis that

crippled the U.S. and other economies in 2008 may be greater control of

the money supply by the Fed.

Bank Finance and a Fractional Reserve System

Bank

finance lies at the heart of the process through which money is created.

To understand money creation, we need to understand some of the basics

of bank finance.

Banks

accept deposits and issue checks to the owners of those deposits. Banks

use the money collected from depositors to make loans. The bank’s

financial picture at a given time can be depicted using a simplified

balance sheet, which is a financial statement showing assets, liabilities, and net worth.

Assets are anything of value.

Liabilities are obligations to other parties.

Net worth

equals assets less liabilities. All these are given dollar values in a

firm’s balance sheet. The sum of liabilities plus net worth therefore

must equal the sum of all assets. On a balance sheet, assets are listed

on the left, liabilities and net worth on the right.

The

main way that banks earn profits is through issuing loans. Because their

depositors do not typically all ask for the entire amount of their

deposits back at the same time, banks lend out most of the deposits they

have collected—to companies seeking to expand their operations, to

people buying cars or homes, and so on. Banks keep only a fraction of

their deposits as cash in their vaults and in deposits with the Fed.

These assets are called

reserves.

Banks lend out the rest of their deposits. A system in which banks hold

reserves whose value is less than the sum of claims outstanding on

those reserves is called a

fractional reserve banking system.

Table 9.1 “The Consolidated Balance Sheet for U.S. Commercial Banks, January 2012”

shows a consolidated balance sheet for commercial banks in the United

States for January 2012. Banks hold reserves against the liabilities

represented by their checkable deposits. Notice that these reserves were

a small fraction of total deposit liabilities of that month. Most bank

assets are in the form of loans.

Table 9.1 The Consolidated Balance Sheet for U.S. Commercial Banks, January 2012

| Assets |

Liabilities and Net Worth |

| Reserves |

$1,592.9 |

Checkable deposits |

$8,517.9 |

| Other assets |

$1,316.2 |

Borrowings |

1,588.1 |

| Loans |

$7,042.0 |

Other liabilities |

1,049.4 |

| Securities |

$2,546.1 |

|

|

| Total assets |

$12,497.2 |

Total liabilities |

$11,155.4 |

|

Net worth |

$1,341.8 |

This balance sheet for all commercial banks in the

United States shows their financial situation in billions of dollars,

seasonally adjusted, in January 2012.

Source: Federal Reserve Statistical Release H.8 (February 17, 2012).

In the next section, we will learn that money is created when banks issue loans.

Money Creation

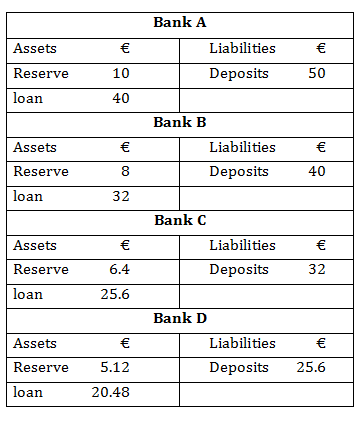

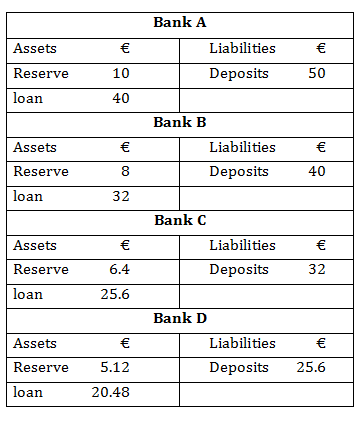

To

understand the process of money creation today, let us create a

hypothetical system of banks. We will focus on three banks in this

system: Acme Bank, Bellville Bank, and Clarkston Bank. Assume that all

banks are required to hold reserves equal to 10% of their checkable

deposits. The quantity of reserves banks are required to hold is called

required reserves. The reserve requirement is expressed as a

required reserve ratio;

it specifies the ratio of reserves to checkable deposits a bank must

maintain. Banks may hold reserves in excess of the required level; such

reserves are called

excess reserves. Excess reserves plus required reserves equal total reserves.

Because

banks earn relatively little interest on their reserves held on deposit

with the Federal Reserve, we shall assume that they seek to hold no

excess reserves. When a bank’s excess reserves equal zero, it is

loaned up.

Finally, we shall ignore assets other than reserves and loans and

deposits other than checkable deposits. To simplify the analysis

further, we shall suppose that banks have no net worth; their assets are

equal to their liabilities.

Let us

suppose that every bank in our imaginary system begins with $1,000 in

reserves, $9,000 in loans outstanding, and $10,000 in checkable deposit

balances held by customers. The balance sheet for one of these banks,

Acme Bank, is shown in Table 9.2 “A Balance Sheet for Acme Bank”.

The required reserve ratio is 0.1: Each bank must have reserves equal

to 10% of its checkable deposits. Because reserves equal required

reserves, excess reserves equal zero. Each bank is loaned up.

Table 9.2 A Balance Sheet for Acme Bank

| Acme Bank |

| Assets |

Liabilities |

| Reserves |

$1,000 |

Deposits |

$10,000 |

| Loans |

$9,000 |

|

We assume that all banks in a hypothetical system of

banks have $1,000 in reserves, $10,000 in checkable deposits, and $9,000

in loans. With a 10% reserve requirement, each bank is loaned up; it

has zero excess reserves.

Acme

Bank, like every other bank in our hypothetical system, initially holds

reserves equal to the level of required reserves. Now suppose one of

Acme Bank’s customers deposits $1,000 in cash in a checking account. The

money goes into the bank’s vault and thus adds to reserves. The

customer now has an additional $1,000 in his or her account. Two

versions of Acme’s balance sheet are given here. The first shows the

changes brought by the customer’s deposit: reserves and checkable

deposits rise by $1,000. The second shows how these changes affect

Acme’s balances. Reserves now equal $2,000 and checkable deposits equal

$11,000. With checkable deposits of $11,000 and a 10% reserve

requirement, Acme is required to hold reserves of $1,100. With reserves

equaling $2,000, Acme has $900 in excess reserves.

At this

stage, there has been no change in the money supply. When the customer

brought in the $1,000 and Acme put the money in the vault, currency in

circulation fell by $1,000. At the same time, the $1,000 was added to

the customer’s checking account balance, so the money supply did not

change.

Figure 9.2

Because

Acme earns only a low interest rate on its excess reserves, we assume

it will try to loan them out. Suppose Acme lends the $900 to one of its

customers. It will make the loan by crediting the customer’s checking

account with $900. Acme’s outstanding loans and checkable deposits rise

by $900. The $900 in checkable deposits is new money; Acme created it

when it issued the $900 loan. Now you know where money comes from—it is

created when a bank issues a loan.

Figure 9.3

Presumably,

the customer who borrowed the $900 did so in order to spend it. That

customer will write a check to someone else, who is likely to bank at

some other bank. Suppose that Acme’s borrower writes a check to a firm

with an account at Bellville Bank. In this set of transactions, Acme’s

checkable deposits fall by $900. The firm that receives the check

deposits it in its account at Bellville Bank, increasing that bank’s

checkable deposits by $900. Bellville Bank now has a check written on an

Acme account. Bellville will submit the check to the Fed, which will

reduce Acme’s deposits with the Fed—its reserves—by $900 and increase

Bellville’s reserves by $900.

Figure 9.4

Notice

that Acme Bank emerges from this round of transactions with $11,000 in

checkable deposits and $1,100 in reserves. It has eliminated its excess

reserves by issuing the loan for $900; Acme is now loaned up. Notice

also that from Acme’s point of view, it has not created any money! It

merely took in a $1,000 deposit and emerged from the process with $1,000

in additional checkable deposits.

The

$900 in new money Acme created when it issued a loan has not vanished—it

is now in an account in Bellville Bank. Like the magician who shows the

audience that the hat from which the rabbit appeared was empty, Acme

can report that it has not created any money. There is a wonderful irony

in the magic of money creation: banks create money when they issue

loans, but no one bank ever seems to keep the money it creates. That is

because money is created within the banking system, not by a single

bank.

The

process of money creation will not end there. Let us go back to

Bellville Bank. Its deposits and reserves rose by $900 when the Acme

check was deposited in a Bellville account. The $900 deposit required an

increase in required reserves of $90. Because Bellville’s reserves rose

by $900, it now has $810 in excess reserves. Just as Acme lent the

amount of its excess reserves, we can expect Bellville to lend this

$810. The next set of balance sheets shows this transaction. Bellville’s

loans and checkable deposits rise by $810.

Figure 9.5

The

$810 that Bellville lent will be spent. Let us suppose it ends up with a

customer who banks at Clarkston Bank. Bellville’s checkable deposits

fall by $810; Clarkston’s rise by the same amount. Clarkston submits the

check to the Fed, which transfers the money from Bellville’s reserve

account to Clarkston’s. Notice that Clarkston’s deposits rise by $810;

Clarkston must increase its reserves by $81. But its reserves have risen

by $810, so it has excess reserves of $729.

Figure 9.6

Notice

that Bellville is now loaned up. And notice that it can report that it

has not created any money either! It took in a $900 deposit, and its

checkable deposits have risen by that same $900. The $810 it created

when it issued a loan is now at Clarkston Bank.

The

process will not end there. Clarkston will lend the $729 it now has in

excess reserves, and the money that has been created will end up at some

other bank, which will then have excess reserves—and create still more

money. And that process will just keep going as long as there are excess

reserves to pass through the banking system in the form of loans. How

much will ultimately be created by the system as a whole? With a 10%

reserve requirement, each dollar in reserves backs up $10 in checkable

deposits. The $1,000 in cash that Acme’s customer brought in adds $1,000

in reserves to the banking system. It can therefore back up an

additional $10,000! In just the three banks we have shown, checkable

deposits have risen by $2,710 ($1,000 at Acme, $900 at Bellville, and

$810 at Clarkston). Additional banks in the system will continue to

create money, up to a maximum of $7,290 among them. Subtracting the

original $1,000 that had been a part of currency in circulation, we see

that the money supply could rise by as much as $9,000.

Heads Up!

Notice that when the

banks received new deposits, they could make new loans only up to the

amount of their excess reserves, not up to the amount of their deposits

and total reserve increases. For example, with the new deposit of

$1,000, Acme Bank was able to make additional loans of $900. If instead

it made new loans equal to its increase in total reserves, then after

the customers who received new loans wrote checks to others, its

reserves would be less than the required amount. In the case of Acme,

had it lent out an additional $1,000, after checks were written against

the new loans, it would have been left with only $1,000 in reserves

against $11,000 in deposits, for a reserve ratio of only 0.09, which is

less than the required reserve ratio of 0.1 in the example.

The Deposit Multiplier

We can relate the potential increase in the money supply to the change in reserves that created it using the

deposit multiplier (

md), which equals the ratio of the maximum possible change in checkable deposits (∆

D) to the change in reserves (∆

R). In our example, the deposit multiplier was 10:

Equation 9.1

To see how the deposit multiplier md is related to the required reserve ratio, we use the fact that if banks in the economy are loaned up, then reserves, R, equal the required reserve ratio (rrr) times checkable deposits, D:

Equation 9.2

A

change in reserves produces a change in loans and a change in checkable

deposits. Once banks are fully loaned up, the change in reserves, ∆R, will equal the required reserve ratio times the change in deposits, ∆D:

Equation 9.3

Solving for ∆D, we have

Equation 9.4

Dividing both sides by ∆R, we see that the deposit multiplier, md, is 1/rrr:

Equation 9.5

The deposit multiplier is thus given by the reciprocal of the required reserve ratio.

With a required reserve ratio of 0.1, the deposit multiplier is 10. A

required reserve ratio of 0.2 would produce a deposit multiplier of 5.

The higher the required reserve ratio, the lower the deposit multiplier.

Actual

increases in checkable deposits will not be nearly as great as suggested

by the deposit multiplier. That is because the artificial conditions of

our example are not met in the real world. Some banks hold excess

reserves, customers withdraw cash, and some loan proceeds are not spent.

Each of these factors reduces the degree to which checkable deposits

are affected by an increase in reserves. The basic mechanism, however,

is the one described in our example, and it remains the case that

checkable deposits increase by a multiple of an increase in reserves.

The

entire process of money creation can work in reverse. When you withdraw

cash from your bank, you reduce the bank’s reserves. Just as a deposit

at Acme Bank increases the money supply by a multiple of the original

deposit, your withdrawal reduces the money supply by a multiple of the

amount you withdraw. And just as money is created when banks issue

loans, it is destroyed as the loans are repaid. A loan payment reduces

checkable deposits; it thus reduces the money supply.

Suppose,

for example, that the Acme Bank customer who borrowed the $900 makes a

$100 payment on the loan. Only part of the payment will reduce the loan

balance; part will be interest. Suppose $30 of the payment is for

interest, while the remaining $70 reduces the loan balance. The effect

of the payment on Acme’s balance sheet is shown below. Checkable

deposits fall by $100, loans fall by $70, and net worth rises by the

amount of the interest payment, $30.

Similar

to the process of money creation, the money reduction process decreases

checkable deposits by, at most, the amount of the reduction in deposits

times the deposit multiplier.

Figure 9.7

The Regulation of Banks

Banks

are among the most heavily regulated of financial institutions. They are

regulated in part to protect individual depositors against corrupt

business practices. Banks are also susceptible to crises of confidence.

Because their reserves equal only a fraction of their deposit

liabilities, an effort by customers to get all their cash out of a bank

could force it to fail. A few poorly managed banks could create such a

crisis, leading people to try to withdraw their funds from well-managed

banks. Another reason for the high degree of regulation is that

variations in the quantity of money have important effects on the

economy as a whole, and banks are the institutions through which money

is created.

Deposit Insurance

From

a customer’s point of view, the most important form of regulation comes

in the form of deposit insurance. For commercial banks, this insurance

is provided by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

Insurance funds are maintained through a premium assessed on banks for

every $100 of bank deposits.

If a

commercial bank fails, the FDIC guarantees to reimburse depositors up

to $250,000 (raised from $100,000 during the financial crisis of 2008)

per insured bank, for each account ownership category. From a

depositor’s point of view, therefore, it is not necessary to worry about

a bank’s safety.

One

difficulty this insurance creates, however, is that it may induce the

officers of a bank to take more risks. With a federal agency on hand to

bail them out if they fail, the costs of failure are reduced. Bank

officers can thus be expected to take more risks than they would

otherwise, which, in turn, makes failure more likely. In addition,

depositors, knowing that their deposits are insured, may not scrutinize

the banks’ lending activities as carefully as they would if they felt

that unwise loans could result in the loss of their deposits.

Thus,

banks present us with a fundamental dilemma. A fractional reserve

system means that banks can operate only if their customers maintain

their confidence in them. If bank customers lose confidence, they are

likely to try to withdraw their funds. But with a fractional reserve

system, a bank actually holds funds in reserve equal to only a small

fraction of its deposit liabilities. If its customers think a bank will

fail and try to withdraw their cash, the bank is likely to fail. Bank

panics, in which frightened customers rush to withdraw their deposits,

contributed to the failure of one-third of the nation’s banks between

1929 and 1933. Deposit insurance was introduced in large part to give

people confidence in their banks and to prevent failure. But the deposit

insurance that seeks to prevent bank failures may lead to less careful

management—and thus encourage bank failure.

Regulation to Prevent Bank Failure

To

reduce the number of bank failures, banks are limited in what they can

do. Banks are required to maintain a minimum level of net worth as a

fraction of total assets. Regulators from the FDIC regularly perform

audits and other checks of individual banks to ensure they are operating

safely.

The

FDIC has the power to close a bank whose net worth has fallen below the

required level. In practice, it typically acts to close a bank when it

becomes insolvent, that is, when its net worth becomes negative.

Negative net worth implies that the bank’s liabilities exceed its

assets.

When

the FDIC closes a bank, it arranges for depositors to receive their

funds. When the bank’s funds are insufficient to return customers’

deposits, the FDIC uses money from the insurance fund for this purpose.

Alternatively, the FDIC may arrange for another bank to purchase the

failed bank. The FDIC, however, continues to guarantee that depositors

will not lose any money.

Regulation in Response to Financial Crises

In

the aftermath of the Great Depression and the banking crisis that

accompanied it, laws were passed to try to make the banking system

safer. The Glass-Steagall Act of that period created the FDIC and the

separation between commercial banks and investment banks. Over time, the

financial system in the United States and in other countries began to

change, and in 1999, a law was passed in the United States that

essentially repealed the part of the Glass-Steagall Act that had created

the separation between commercial and investment banking. Proponents of

eliminating the separation between the two types of banks argued that

banks could better diversify their portfolios if allowed to participate

in other parts of the financial markets and that banks in other

countries operated without such a separation.

Similar

to the reaction to the banking crisis of the 1930s, the financial

crisis of 2008 and the Great Recession led to calls for financial market

reform. The result was the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer

Protection Act, usually referred to as the Dodd-Frank Act, which was

passed in July 2010. More than 2,000 pages in length, the regulations to

implement most provisions of this act were set to take place over a

nearly two-year period, with some provisions expected to take even

longer to implement. This act created the Consumer Financial Protection

Agency to oversee and regulate various aspects of consumer credit

markets, such as credit card and bank fees and mortgage contracts. It

also created the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) to assess

risks for the entire financial industry. The FSOC can recommend that a

nonbank financial firm, such as a hedge fund that is perhaps threatening

the stability of the financial system (i.e., getting “too big to

fail”), become regulated by the Federal Reserve. If such firms do become

insolvent, a process of liquidation similar to what occurs when the

FDIC takes over a bank can be applied. The Dodd-Frank Act also calls for

implementation of the Volcker rule, which was named after the former

chair of the Fed who argued the case. The Volcker rule is meant to ban

banks from using depositors’ funds to engage in certain types of

speculative investments to try to enhance the profits of the bank, at

least partly reinstating the separation between commercial and

investment banking that the Glass-Steagall Act had created. There are

many other provisions in this wide-sweeping legislation that are

designed to improve oversight of nonbank financial institutions,

increase transparency in the operation of various forms of financial

instruments, regulate credit rating agencies such as Moody’s and

Standard & Poor’s, and so on. Given the lag time associated with

fully implementing the legislation, it will probably be many years

before its impact can be fully assessed.